Should you add water to whisky?

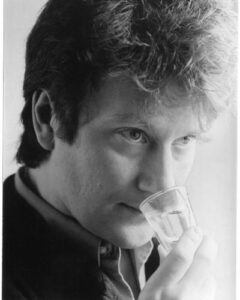

We asked whisky writer Ian Wisniewski – whose book The Whisky Dictionary comes out on September 5th – for his thoughts on a question we get asked a lot by visitors to the Scotch Whisky Experience: should you add water to whisky?

“Whisky lovers can be divided into various groups. Some are committed to malts, others always pour a blend. Some crave peated malts, while others won’t even try. Another dividing line is between those who automatically add water, and those who believe that water can only compromise (or even decimate) the experience.

Adding water is often assumed to be the right thing to do, in order to ‘open up’ a whisky. This familiar advice suggests that adding water promotes a more comprehensive experience. Sounds great. But it’s more accurate to say adding water promotes a different experience.

A key influence on the flavour profile of a whisky is the alcoholic strength. This is because different flavour compounds change from being soluble to insoluble at particular strengths. When a flavour compound is soluble it is ‘dissolved’ within the whisky, and consequently not discernible. When a flavour compound becomes insoluble it exists as an independent entity within the whisky, and shows as a flavour.

A higher alcoholic strength typically delivers richer, more concentrated flavours, such as dried fruit and vanilla, compared to a lower strength which promotes lighter notes, such as citrus. Meanwhile, phenolic compounds (smokey, peaty notes) become progressively mellower and diminish as water is added.

With each whisky offering a range of flavour profiles, depending on the degree of dilution, there is only one way to discover where the ideal flavour lies. A fascinating experiment is to initially taste a whisky neat (with higher strength whiskies, the sheer intensity of alcohol can numb the palate and limit a tasting experience). Nevertheless, this acts as a ‘control’ and point of comparison for dilution, and the quest for the ultimate version.

Water should be still spring water, ie. without the discernible characteristics of mineral water which would confuse the experiment. After adding a drop of water, with a pipette offering ultimate control, the whisky can be re-tasted, and then again with two drops of water, and so on. This is the convenient version of the experiment. A more scientific version is to fill several glasses of the same size and shape, with equal amounts of whisky, and taste the first glass neat, taste the second with one drop of water, the third with two drops, and so on. This compares the effect of varying degrees of dilution on the same amount of whisky, but requires far more glassware.

Whether, and how much water delivers the ideal flavour profile, depends of course on personal preference. My experience is that whisky at bottling strength usually reveals a sequence of individual flavours, each having their moment in the spotlight, which I really like. Adding water often ‘integrates’ the flavours into an evenly balanced package, with the flavours appearing simultaneously (rather than individually). I also find oak notes can become more pronounced, while phenolic character (ie. smoke and peat) diminishes. I love phenolics, but the more supple the oak notes the better.

Dilution also effects a significant change in the mouthfeel. At bottling strength the texture of a whisky can range from soft and delicate to rounder, fuller-bodied and even lightly creamy. As mouthfeel is the delivery vehicle for flavour I consider it an integral part of the experience, and diluting reduces the individuality of the mouthfeel (which I consider a great shame).

Another consideration is that adding water reduces the level of intensity that a whisky has, and replaces it with mellowness. This could be considered a benefit, or reason for regret. I prefer intensity. Always.”

Adapted from The Whisky Dictionary (Octopus Publishing) by Ian Wisniewski.